Tennessee is the LEAST active state in the nation and 88% of Nashville's roads are unsafe for pedestrians and bike riders...

Tennessee's obesity rate is over 30%.

If you see the connection...you will understand why it is critical to ask local and state leaders to fund the highest quality sidewalks possible.

The Nashville Area MPO: Linking transportation & public health

How setting criteria for project selection transformed a regional transportation plan

Over the last several years, Nashville’s regional leaders have been trailblazers in using health indicators as one key screen for choosing projects marked by their 2035 Regional Transportation Plan. The focus on the connection between transportation and public health transformed their plan; where in the previous plan approximately 2 percent of projects incorporated features to provide safe walking and biking, in the most recent version nearly 70 percent include those elements.

The journey toward identifying and adopting the criteria they would use to select projects involved blazing their own path in an emerging practice.

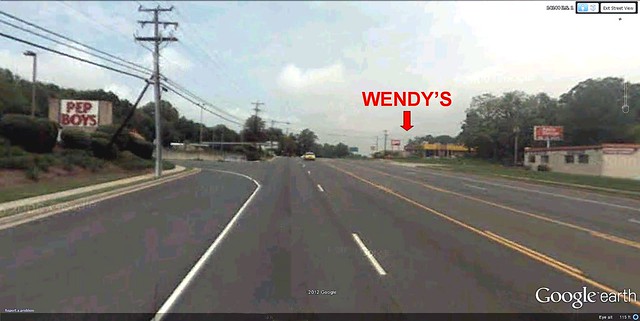

They went beyond the typical practice of Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs) in considering health only in regards to air quality and road safety. Instead, they began to also recognize a much broader interplay of transportation and public health by considering the role of transportation in increasing physical activity and access to destinations (e.g. employment centers and healthcare facilities), and in improving overall quality of life.

Flickr photo by Prayitno. https://www.flickr.com/photos/prayitnophotography/17180174647/

A public health crisis and a clear public vote of confidence

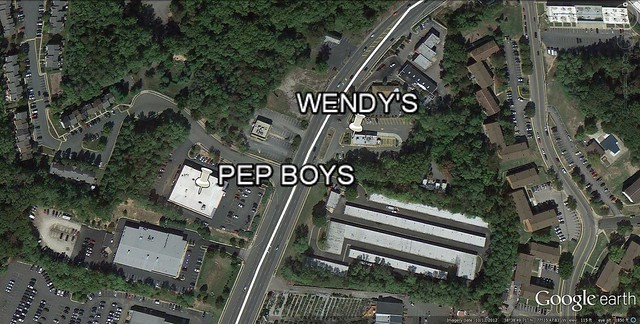

The story of how the five-county Nashville Area MPO (pop. 1.5 million) became a leader in using health-related criteria to shape its Regional Transportation Plan begins in the late 2000s with a recognized public health crisis.Tennessee is the least active state in the nation with 61 percent of adults failing to get adequate physical activity. Safe streets and sidewalks for walking or bicycling are in short supply across the broader Nashville region. A 2009 study by the MPO found that 88 percent of the region’s roads were unsafe for people on foot or bicycle.

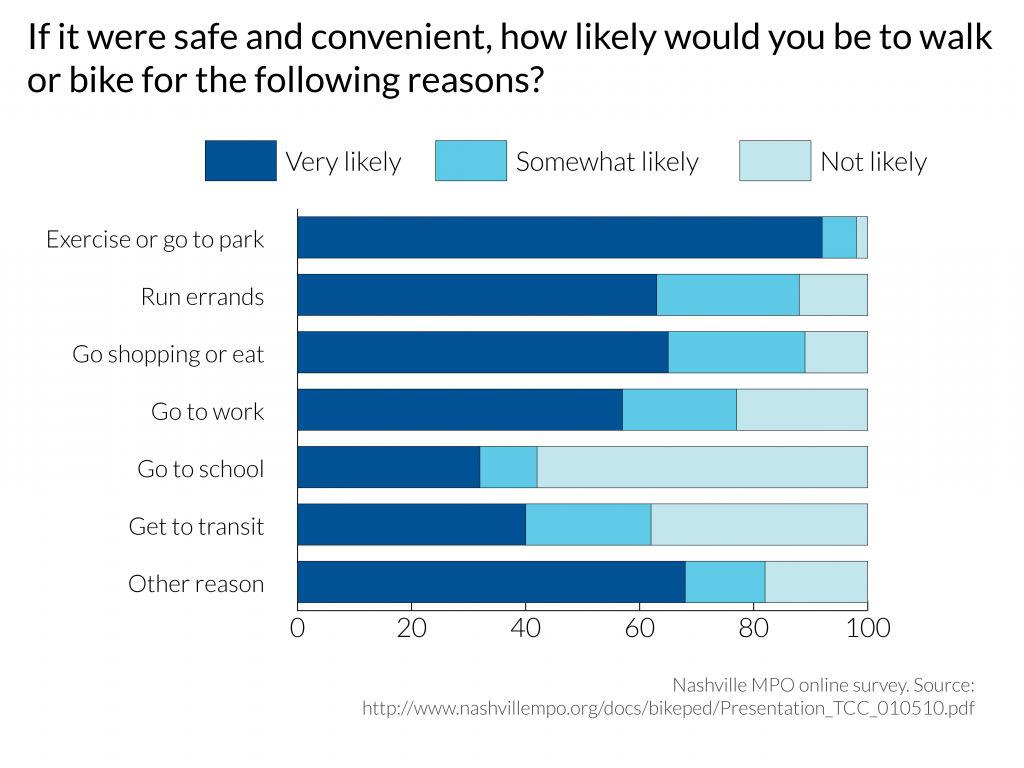

The eye-opening results of a 2010 MPO attitudinal survey of residents helped push the The Nashville MPO toward this eventual shift in policy toward using health-related criteria to shape their long-term plan and select projects, revealing deep public support for increasing opportunities to use public transportation options and safely walk or bike around the region.

In this survey of 1,100 randomly selected households, Nashville region residents voiced the greatest support for providing more public transit, followed by increasing active transportation (walking and biking) options, and also for preserving existing roadways and adding sidewalks. The MPO then moved on to developing a process to score and select transportation projects to address the desire from the public for having more of these facilities, with improving residents’ health as a central component.

Photos courtesy of Stacy Proctor, The Shade Parade. http://shadeparadenashville.blogspot.com

When the MPO began considering goals for its 2035 plan (adopted in 2010), the staff and leadership considered health concerns beyond obesity to include asthma and other air-quality related diseases, traffic injuries and health conditions associated with lack of exercise. In considering health along with other quality of life goals, they found substantial overlap with solutions for economic and environmental sustainability.

The MPO developed four desired outcomes from transportation investment with links to public health and well-being: (1) levels of physical activity, (2) air quality, (3) safety and (4) and addressing disparate impacts on vulnerable or disadvantaged populations, including children, the elderly and low-income neighborhoods.

The MPO then zeroed in on several core objectives:

Investing in communities to provide a safe and convenient option for walking and biking.

Investing in building a modern regional transit network.

Adopting a “fix-it-first” approach that emphasizes repair and improvement of existing roads before constructing new ones.

Shifting investment strategies towards a diversity of transportation options, rather than sole focus on road capacity.

Use transportation improvements to develop a sense of place (not explicitly referred to in the 2035 plan, but a focus of the MPO’s ongoing efforts).

All of these changes in process came from the understanding that the way communities are designed and their transportation systems have substantial impacts on the health and well being of their residents.

Matching funding to new priorities

Over the course of the next 25 years a substantial portion of the MPO’s $7 billion transportation budget is targeted towards expanding the active transportation network in Middle Tennessee.

The MPO’s largest source of federal funds comes from what’s known as the Surface Transportation Program. The Nashville Area MPO is dedicating 15 percent of those STP funds to their newly-created Active Transportation Program (ATP) for bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure, another 10 percent to match Federal Transit Administration funds for supporting transit investments, and additional STP funds toward projects that incorporate Complete Streets elements.

All told, under the 2035 Regional Transportation Plan, 70 percent of the adopted roadway projects include active transportation infrastructure.

Scoring and evaluating projects

In scoring projects for possible funding, MPO officials are assigning more points to those that promote physical activity in existing communities, as well as those that provide multimodal access and connections, and that improve the conditions for people on foot.

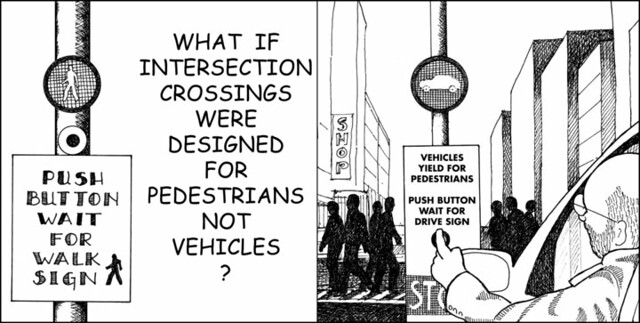

In calculating project benefits, areas with more vulnerable residents (health-wise) benefit the most from having new opportunities to walk or bike safely. Health disparities tend to be highest in areas that are more economically disadvantaged, which the MPO measured by determining the areas that have a larger percentage Hispanic and minority populations, higher rates of poverty, physical disability, single parent households, zero-car households, and areas with higher percentages of people that have limited English proficiency.

Under the scoring system, 60 percent of the criteria relate to elements of active transportation, health, the environment, safety and congestion. The congestion score is weighted in favor of project that can improve health through additional non-motorized road capacity (i.e, sidewalks and bike lanes, etc.), safety (i.e. crosswalks, bump-outs, etc) and navigation enhancements for people using non-motorized modes.

To measure progress and assess what’s having an impact and where on the health of Nashville residents, the MPO is collecting data to provide baseline evidence for policy benchmarking and, over time, provide a measuring stick.

Giving the people what they want

Nashville area residents react positively to the idea of safer and more convenient walking and biking infrastructure. Even with current inadequacies in walking and bicycling facilities in the MPO’s area, 92 percent of the surveyed public would be willing to use bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure to exercise or go to a park; 66 percent to shop or eat out; 65 percent to run errands; and 55 percent to bike and walk to work if it were safe and convenient, according to this survey from the MPO.

The Nashville Area MPO’s new criteria for scoring and choosing projects have transformed the project selection process by providing a far more holistic analysis of the benefits created by each transportation project and how projects compared to the hundreds of others competing for federal funds. With limited resources available to support transportation investment, the Nashville Area MPO elevates projects that score the highest on multiple objectives, with health and equity serving as important components in that evaluation process.

To view the Project Evaluation Criteria that the Nashville Area MPO used in the 2035 Regional Transportation Plan, visit the following link: http://nashvillempo.org/docs/lrtp/2035rtp/Docs/MPO_Scoring_031710.pdf

To view the entire 2035 Regional Transportation Plan: http://www.nashvillempo.org/docs/lrtp/2035rtp/Docs/2035_Doc/2035Plan_Complete.pdf